Ottoman twilight: The last pashas of Ioannina

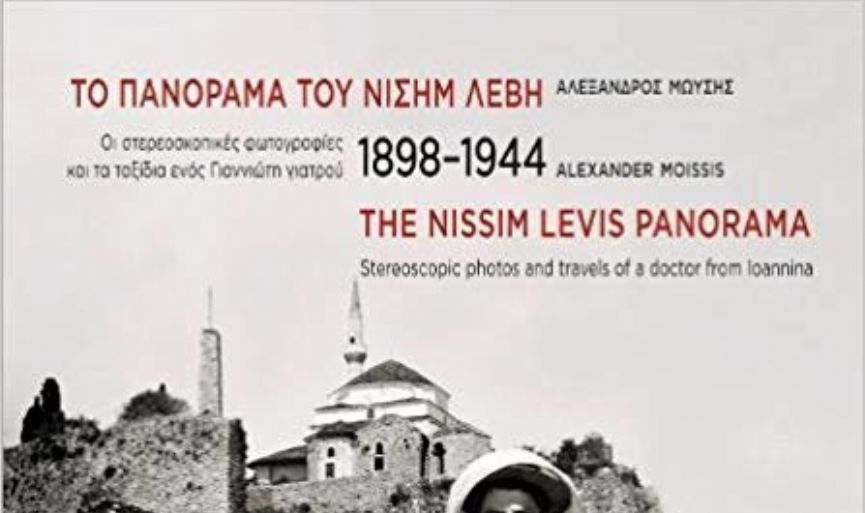

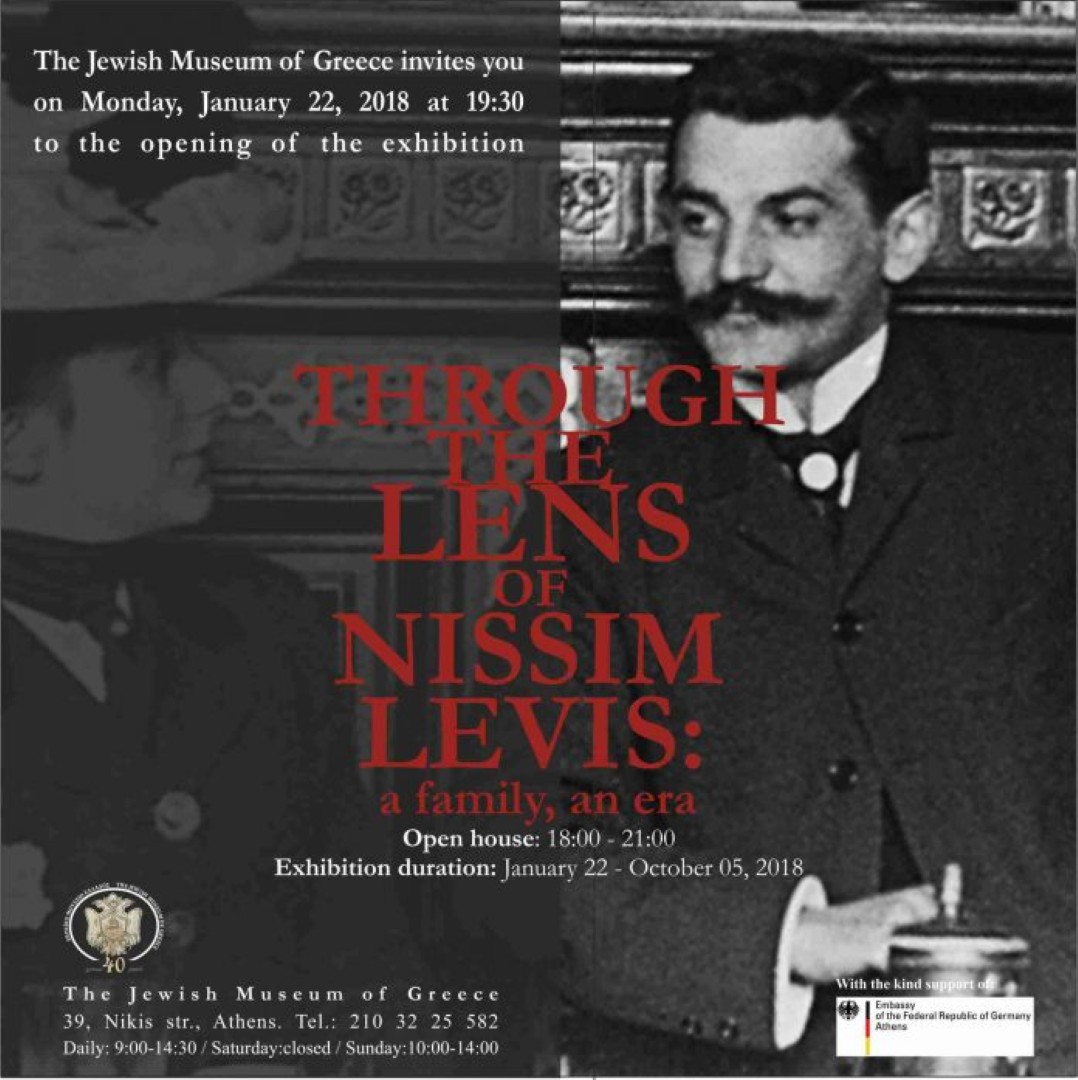

In the last years of Ottoman rule, Nissim Levis, a doctor from the wealthiest family in Ioannina, photographed his city, famed for its silver, silk and separatism under the Lion, Ali Pasha of Tepelene. In Athens, the Jewish Museum of Greece is exhibiting his stereoscopic prints until October 5.

Matt Hanson / Athens

The author and businessman Alexander Moissis retraced the footsteps of his great-grandmother’s uncle Nissim Levis in Ioannina, a small city in Greece’s mountainous northwest. He walked down the rough stone steps of overlapping empires, a snarl of ruins smoothed by metal ramps leading to the 10th century walls that defended the Despotate of Epirus, the 13th century Byzantine successor state that wrote Ioannina into history.

Moissis looked back at the vacant museum of Fethiye Mosque behind a row of iron cannons against the alpine horizon above Pamvotis Lake, once furnished to protect a Royal Pavilion that now houses the city’s Byzantine Museum. In a district still known in the tongue of its former Turkish lords as Iç Kale (the inner castle), the southeastern acropolis of Ioannina rises over 30 square kilometers of ancient urban space above a panoramic high ground where the seraglio and harem of the pashas ruled under the Sultanate of Constantinople.

It was September of 2017, as Jews around the world convened for Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. The indigenous Greek-speaking community of Ioannina preserves Romaniote culture with peerless depth, gathering once a year for the sole remaining Jewish service at the Old Synagogue, said to have been built on a foundation at least as old as the surrounding walls on a narrow alley inside the castle district. Lit by Byzantine lamps and serenaded in mournful, Gregorian-like chants of atonement sung by cantor Haim Ischakis, a full congregation complemented by diaspora solidarity sat, prayed and remembered.

In the shadow of historic cookhouses along the western bastion of Byzantine fortifications dramatically restored during the Ottoman era and renovated for the Silversmithing Museum’s 2016 inauguration, Moissis met with colleagues for secular purposes, to discuss the American distribution of his book, “The Nissim Levis Panorama: Stereoscopic Photos and Travels of a Doctor from Ioannina” with Marcia Ikonomopoulos, the director of Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue Museum in Manhattan, housed in the only active Romaniote synagogue in the Western Hemisphere. Inspired by his roots in Ioannina as a Greek educated in Athens College and MIT, he returned to the upland airs of his family history with smiling confidence, optimistic about his book’s reception in New York, with its world-class publishers and voracious readers. Worldly life runs parallel, and often independent from orthodox religion for Romaniotes, especially from Ioannina.

Romaniote life today

“First of all, it is very difficult to have a complete religious life in Ioannina, and not only in Ioannina, in all other Greek cities with the exception of Athens or Salonika. We have to adjust our lives to the specific, prevailing conditions in every society. So, we are not very strict,” said Moses Elisaf, professor of internal medicine and the president of the Jewish Community of Ioannina, in a 2016 interview with an American traveler and researcher exploring his Romaniote heritage, in which he discussed the secular nature of Jewish life in Ioannina. “We do not to focus on typical religious rules, but on history, tradition, and science. We try to discuss Talmud and Torah, not as religious texts, but for their meaning, for what they teach us in our everyday lives.”

And yet, for Moissis, who found entrepreneurial success in Silicon Valley, his ancestors practically rediscovered him through a nonlinear logic as confounding as the principles of faith. Such truths are echoed in the living folklore of Native American elders, who remind soul seekers that the late departed also search for the living. Hiette and Asher, the great-grandparents of Moissis, survived the Holocaust and returned to the postwar Ioannina of 1945 very much like ghosts in a city that denied its Holocaust.

As the red sun rose, looters preyed on the downtown mansions of the bourgeois Levi family once headed by patriarch Davidjon Effendi (his personal medals included the Osman Devlet Nisanư, Hilal Nisanư and Nisan-i Initiya). Among the spoils were 500 unseparated glass slides kept in a Richard Taxiphote projector owned by Effendi’s fifth son, Nissim Levis. In the eyes of ignorant thieves, the projector would seem like a piece of wooden furniture. A year after it was stolen, the projector appeared in Ioannina for the amusement of lakeside strollers. To the astonishment of Hiette and Asher Moissis, they found the turn-of-the-century invention there, popularly called a “panorama”.

After gazing at the snowcapped Pindos mountains reflected in the glassy waters of the lake that first and bittersweet postwar spring, they paid what seemed a reasonable amount to look inside the panorama. The small, countrified city had no movie house to speak of and they were keen to see foreign lands far from Greece, as the vendor promised. It was not long before they recognized the photos. Hiette saw the handiwork of her uncle Nissim. And as she clicked the shutter, changing through slides that chronicled his years in France, Italy and across the region of Epirus surrounding Ioannina, she could not see the pictures clearly anymore. Then not at all. Her eyes blurred with the tragedy of his loss in Auschwitz, where 1,850 of her fellow Jews from Ioannina also perished.

In the lion’s den

Hungarian novelist Mór Jókai wrote “Lion of Janina: The Last Days of the Janissaries” to capture the orientalist intrigue of the city’s Ottoman past. First published in 1897, it is subtitled, “A Turkish Novel” and translated by R. Nisbet Bain, soon released in New York and London by Harper & Brothers in 1898. Its riveting, pulpy narrative is chock-full of that delicious blend of exoticism and romance that fired the pages of the early modern novel for readers in for a romp. Hungarians had espied the Ottoman imagination with a distinct brand of suspicion and curiosity, as one of the occupied territories of the Turkish Sultan from 1541 to 1699. In literature and with a creative lens, many writers fictionalized Ali Pasha as a premodern anti-hero, from Byron’s “Child Harold’s Pilgrimage” to Balzac’s “Lost Illusions”. Unassimilated by the West, the Lion of Janina also symbolized nonconformism against the East.

“Manifold and monstrous as were Ali’s crimes, his astonishing ability and splendid courage lend a sort of savage sublimity even to his blood-stained career, and, indeed, the dogged valor with which the octogenarian warrior defended himself at the last in his stronghold against the whole might of the Ottoman Empire almost without a parallel in history,” wrote the translator R. Nisbet Bain to preface Jókai’s 1898 edition, which reads: “Better to perish in the deep void than be condemned to the embraces of Ali Pasha...[he] himself had built the whole citadel of Janina, and had been wise enough, as soon as the fortress was finished to at once and quietly remove all the builders and architects who had had anything to do with it, so that he only knew all the secrets of the place.”

The year Jókai enjoyed literary fame from the bookshops of Manhattan to the salons of Bloomsbury, 23-year-old Nissim Levis picked up a camera with only a year left before graduating from medical school in France. He returned home to Ioannina and began photographing the last years of nearly five Ottoman centuries, and continued with runaway enthusiasm until the Nazis murdered him and his family. On display until October 5th a short walk from Hadrian’s Arch and the National Garden in Athens, the Jewish Museum of Greece curated the life’s work of Nissim Levis after the book by Alexander Moissis, whose father Raphael started the collection. The exhibit has a technological focus, highlighting the influence of early 20th century masters like Yiannis Manakis, who had an early photography studio in Ioannina and is known for having shot the first ever motion picture from the Balkans.

The museum director and exhibition curator Zanet Battinou led a team of researchers, designers, and archivists to open, “Through the lens of Nissim Levis: a family, an era” with a surprise element, bridging photographic history to the present. Through a clever contraption, viewers snap smartphone shots of the double-image prints that Levis developed, to see through a new “panorama” device that recreates the 3-D effect of stereoscopy. It is stunning to examine the lives of the last generation of Ottoman Jews in Greece as they stand in the rustic countryside of lands that would change hands, with people whose lives were too brief.

Related Newsss ss