The younger generation now should reclaim Judeo-Spanish

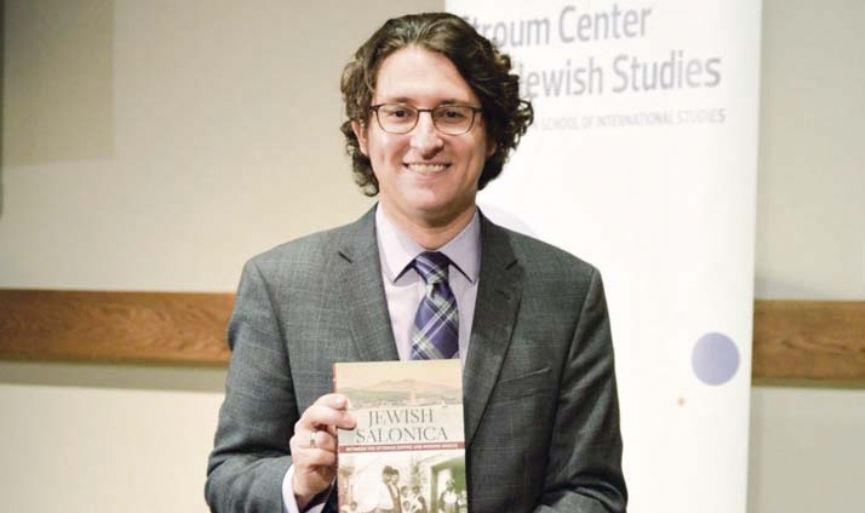

Following my arrival to Seattle in September 2014 to pursue my doctoral studies at the University of Washington, I met with Professor Naar at his office. While I was completing my masters thesis in London a year ago, I contacted him. A couple of months later I was in his office, meeting my doctoral thesis advisor for the next six years. I still remember our talk on stuffed vine leaves and how to find them in Seattle. This is an interview on Professor Naar´s new book Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece, Judeo-Spanish, and the situation of Sephardic studies in the academia. At the same time, this interview can be read as a short story of identity, memory, and space.

Canan Bolel

What got you interested in history, Jewish history particularly?

As a child growing up in New Jersey, I was always intrigued by the family photos depicting ancestors dressed in Ottoman garb: my great grandfather, Rabbi Benjamin Naar, bearded and befezzed; and my great grandmother, Rachel (née Nefussi), dressed in kofya and devantal. Among the older relatives, mostly from Salonica, plus a few from Izmir, Canakkale, and Plovdiv, I heard Judeo-Spanish spoken at their homes and their synagogue, although it was a language I could not initially understand. Their kitchens smelled of borekas and pastel and keftikas. I was drawn not only to the flavors and aromas but also the stories of the old world, a world that I felt an affinity to even though it was not fully mine. Wanting to bridge the divide that separated me from that world, and out of a desire to better understand its present-day impact, I began to delve into the study of Sephardic Jewish history.

What do you think about the establishment and current condition of Sephardic Studies in the United States?

As I began my studies, I discovered that the experience of Jews from the Ottoman Empire was not included in the mainstream Jewish studies or general history curricula at American universities. I eventually found my way to Stanford University to pursue my PhD under the direction of Istanbul-born Aron Rodrigue, the premier scholar of Sephardic history in the United States and the first to thoroughly incorporate Ottoman Jewish history into the university setting.

Sephardic Studies is on the rise in the United States. Study of the Sephardic experience, especially Jews in the Ottoman Empire, is attractive to students and scholars who are interested in better understanding the nuanced relationships between Jews and Muslims beyond the Israel-Palestine conflict; who want to expand their knowledge of Jewish culture beyond the dominant images of Ashkenazi shtetls and the Yiddish language; and who want to explore interconnections between different cultures across time and geography - a theme reflected in the history of Judeo-Spanish.

University of Washington also has a program in Sephardic Studies. Can you tell us more about the program and your role in it?

In my present position at the University of Washington, I wanted to further the work done by Dr. Rodrigue by ensuring the adequate representation of the Ottoman Jewish experience. Seattle provided a perfect setting as it is home to one of the largest Sephardic Jewish communities in the country whose member trace their roots to Turkey (Marmara, Tekirdag, Istanbul, and Gallipoli) and Greece (Rhodes and Salonica). Members of the community came to me upon my arrival, asking me to decipher family letters and books written in Judeo-Spanish, especially in Hebrew scripts (rashi and soletreo), to help them regain access to their family histories and to the broader narratives they revealed.

With support from community members with surnames like Alhadeff, Almosnino, Benoliel, Franco, and Galanti, as well as the director of the Jackson School of International Studies, Resat Kasaba, a prominent Ottoman sociologist, and the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, we established a program to promote the Sephardic experience among graduate and undergraduate students, to create public programs like International Ladino Day to cater to our local community, and to develop online resources, like a digital library and museum, to educate all those interested in the fate of Sephardic Jewry.

“JUDEO-SPANISH IS EXPERIENCING SOMETHING OF A REVIVAL IN SEATTLE”

Speaking of Judeo-Spanish, some see Judeo-Spanish as a dying language whereas it is lively in Seattle more than ever. Do you agree?

Judeo-Spanish is experiencing something of a “revival” in Seattle, but we are not seeing its return as a living vernacular of everyday life. Rather, Judeo-Spanish has entered its “post-vernacular” phase: it will not be the language of daily communication, but has acquired a special symbolic value as a marker of Sephardic identity. New generations will probably not be fully immersed in Judeo-Spanish as their ancestors were, but rather their daily lives may be infused with key vocabulary and expressions – ke haber? echar lashon, nochada buena, etc; the two Sephardic synagogues may continue to use Judeo-Spanish in the liturgy; and the university will take on an increasingly important role to perpetuate and disseminate knowledge about the language.

The younger generation of descendants of Judeo-Spanish speakers is no longer engaged in linguistic “preservation” as they have already lost the language; their job is now to “reclaim” the language and determine in which domains of their life, if any, the language ought to play a role as a conscious expression of Sephardic identity in the 21st century.

What is your relationship with Judeo-Spanish on a personal level? Did you hear Judeo-Spanish while growing up; do you speak Judeo-Spanish with your son?

The future of the Judeo-Spanish is also of great personal significance. I am trying to speak with my son, Vidal (Haim), who is one year old, in Judeo-Spanish. I am what linguists call a “heritage speaker”-not a native speaker- although I have studied Judeo-Spanish for fifteen years now and spoke regularly in the language with my nono prior to his death in 2008. To speak in the lingua nona (grandparent tongue) rather than the lingua madre (mother tongue) will be very challenging especially as there are not yet any others of my generation seeking to do the same. I hope that my son will grow up in a world in which Judeo-Spanish infuses every aspect of his life, that he may share greetings, sing songs, chant prayers, and perhaps tell some stories. If he can do as much, I will be satisfied; I do not have illusions that he will absorb the language as a native speaker, although the more comfort he has with it, the more thrilled I would be.

Part of the challenge in promoting a “revival” of Judeo-Spanish stems from the long-standing, generally negative attitudes about the value and legitimacy of the language. Since the nineteenth century, Judeo-Spanish was derided by European observers and Ottoman Jewish intellectuals as a bastard tongue and as a jargon incapable of expressing the concepts of modern civilization. The same feature that was once seen as the weakness of Judeo-Spanish -its “mixed” nature- can now be cast in a positive light within our increasingly globalized world. (Indeed, the Judeo-Spanish term meaning “to mix” is karishtear, which comes from the Turkish karıştırmak). The “non-Spanish” components of Judeo-Spanish can now be viewed as those features that give Judeo-Spanish its distinctive flair and its unique value. Knowledge of Judeo-Spanish can build bridges to many other languages. If you know Judeo-Spanish, you also know a few words of Turkish, Hebrew, Greek, Italian, Arabic, etc., and can begin to connect with members of those other cultures, recognizing not only what separates different peoples but what also links them.

From my perspective, the primary value of Judeo-Spanish in the 21st century is not that it preserves archaic forms of medieval Spanish (although this is also of great interest and should always be emphasized), but rather that it remains a fundamentally hybrid Ottoman language containing ready-made links to other cultures and the building blocks of intercommunal cooperation.

JEWS OF SALONICA

Your book on Salonican Jewry has been published by the Stanford University Press recently. Can you tell us the story behind this book, which is also your doctoral dissertation at Stanford University?

For my book, I wanted to tell the story of the largest Judeo-Spanish speaking community in the world as it confronted the most challenging and devastating moments in its history - namely the end of Ottoman rule and the rise of Modern Greek nationalism, and later the Holocaust. The history had never been told in full, and to the extent that it had, scholars relied primarily on outside sources, such as travelers’ accounts, consular reports, and the correspondence of the Alliance Israélite Universelle. I wanted to tell a different story - one that prioritized the local perspective. The problem was that the archives of the Jewish community of Salonica had all been confiscated by the Nazis and, it was assumed, had mostly been lost. Via a circuitous route, I was able to discover fragments of those archives preserved in New York, Jerusalem, Moscow, and Salonica itself. Relying on these sources plus local newspapers mostly composed in Judeo-Spanish, I wanted to tell the story of Salonica’s Jews in their own words and to restore their voice to the historical record.

While you tell the story of Salonican Jews, you are also telling a very personal story, the story of your family. What is the importance of this book for your family history?

To tell this story not only enabled me to recover the experiences of Salonica’s Jews in modern times, but also to better understand the fate of my own family in the city - why some relatives immigrated in the 1920s to the United States and why others remained in Salonica and ultimately perished in Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943. Such a book also enables me to analyze the broader ramifications of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the rise of new nation-states like Greece, and the contested place of minorities in the modern world - an issue that continues to be of great relevance in contemporary politics.

What were some changes in Salonican Jewish community’s relationship with Jewish communities in Izmir and Istanbul following the formation of Greek and Turkish nation-states? How did people experience this significant change in their daily lives?

In the late Ottoman period, Salonica’s Jews relied on the haham bashi in Istanbul as an intermediary with the Ottoman state and regularly sent delegations to the imperial capital. Jewish newspapers in Istanbul and Izmir played an active role in debating candidates for Salonica’s chief rabbi in 1908, which they deemed a significant issue for “all Ottoman Judaism.” Rabbis in Izmir relied on printers in Salonica to publish their works. All of the different communities from the Balkans and Anatolia were linked not only by political boundaries but also the common language of Judeo-Spanish.

The incorporation of Salonica into Greece contributed to the rupturing of the Judeo-Spanish world that had been unified within the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire. Salonica remerged in this context as a new Jewish capital within the circumscribed borders of Greece upon which smaller Jewish communities in the Greek provinces now depended. Izmir and Istanbul played no role in the succession of Salonica’s chief rabbis in the 1920s or 1930s. The Ottoman Jewish world was now fractured between “Greek” and “Turkish” and, in the case of Rhodes, “Italian” Jewish communities. Ironically, Salonican Jews perpetuated ideals of Jewish Ottomanism even though Ottoman Jewry ceased to exist.

STUDIES ON TURKISH JEWRY

Academic studies on Turkish Jewry have thrived considerably in the last couple decades paralleled by a non-academic interest. What do you think about the situation of the field? Are there still ‘untouched’ areas/topics/groups?

While many new studies on Ottoman and Turkish Jewry have emerged in recent years, in Turkey, the United States, Israel and elsewhere, much still remains to be explored. Many of the smaller Jewish communities - those other than places like Salonica, Istanbul, and Izmir - require their own histories; relationships between provincial communities and urban centers require attention. Greater energy to the cultural dynamics of Ottoman and Turkish Jewry - following in the footsteps of Karen Gerson Sarhon and the work undertaken at the Ottoman Turkish Sephardic Research Center - would also provide an important service as would greater attention to Intercommunal dynamics as well as marginalized populations like women and the poor. The incorporation of Ottoman Jewish narratives into general Jewish history remains essential. The inclusion of Jewish history into Ottoman and Turkish narratives - not only to show that Jews were a model minority (in contrast to the Armenians), but also to show the complexities of the situation - will give voice to those aspects of the dynamic that have been silenced.

Related Newsss ss