"Nothing Can Move People to Tears or to Pure Joy Quite Like Music"

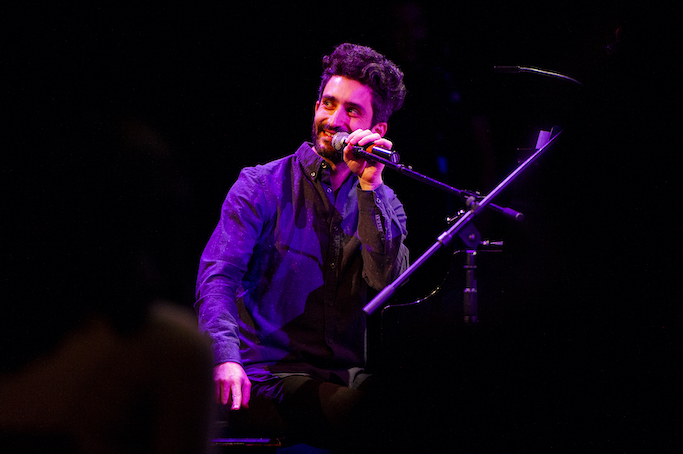

Born in the USA in 1985, Avi Amon, of Turkish origin, is a versatile artist. The operas ´Salonika´ and ´Inşallah / Maşallah´ the composer-pianist-educator Avi Amon composed with inspiration from his roots and his Sephardic culture, made a great impact in the music world. We talked with the artist, whose goal is to rediscover the fading cultures, about his music and his works...

You are a composer, pianist, sound artist, and educator. You are a versatile artist. Is it because you have many interests that you are dealing with so many issues?

This is a very good question! I think I have many interests, yes, but I also think that doing many things is a product of necessity. Not only to earn an income and stay busy as an artist, but to keep my creative brain nimble and flexible.

Each new project forces a new of thinking, and a new set of challenges or restrictions to consider. This last year in the pandemic is a perfect example of this: think of all the ways we’ve been forced to change and adapt, from the smallest thing like going to the grocery store to something more significant like the new ways we connect with our family and community. So much upheaval but also many new modes of thinking, some of which I hope will stick around. The same thing with my career: keep the best, forget the rest. There is no one path to a creative future and I do my best to embrace that chaos.

Where do you get your inspiration from?

One of my goals as a composer is to rediscover pieces of fading cultures, not only to preserve them, but to be an active participant in continuing the traditions, storytelling, and community. As a composer, I am inspired by the sonic landscape of my cultural heritage in the Mediterranean and Middle East. Specifically, the music of the Sephardic Jews and its relation to the music of other peoples who live within the boundaries of the former Ottoman Empire. I work with themes of diaspora and otherness (defined broadly) in my music to create inclusive auditory experiences. I think of sound and music very inclusively and am inspired by everything from bird calls to the sound of a jet engine. I listen to music, of course, but do it very judiciously and specifically when I’m searching for a sound. Film scores, Baroque music, experimental soundscapes, modern R&B and pop, psychedelic 60’s Turkish rock… you name it. But to be honest, I find myself seeking silence the most. Our 2021 selves are constantly inundated with sound, and I find that I need time to clear my ears, and my brain to find real inspiration.

How is your process of turning an idea into music?

My process for writing music is a process of getting lost, creating a big mess of sound and experimentation, and then slowly distilling all of that into something useable. This comes from my background in jazz improvisation and many years of frustrating my classical piano teachers by creating my own versions of Beethoven or Chopin pieces… For any given song or bit of music that makes it into a musical, film, or piece of dance, I may have 50 to 100 more unused samples. They may all be related to an initial impulse I had - a rhythm, a melody, some chords - but they are very different from the finished product. Or perhaps another way of explaining this messy process is that I am chasing after a sound, something I've imagined in my head or felt in the air around us. Usually, I need to think about something for a long time before the music emerges. Every now and then you get a real spark, a gift from the universe, and it comes very quickly. But that is rare and special!

Your work entitled Salonika contains Sephardic elements. Can you tell us about this work?

Salonika is a show very near and dear to my heart, an homage to our history of diaspora and rich cultural heritage, and a meditation on trauma and redemption. My collaborator, Julia Gytri, and I have been working on this show for several years. We are influenced by many Sephardic and Turkish sayings, folktales, and music; Ladino language and melodies are threaded throughout the piece. Introducing an American audience to this can be challenging - even something as simple as beginning a story with "Bir varmış, bir yokmuş [once upon a time in Turkish]" instead of "Once upon a time" can throw someone off and make it feel ‘too foreign.’ Our goal is not to alienate, but to emphasize our shared humanity through these stories, keeping the culture alive. We’ve been fortunate to develop SALONIKA at several theaters across the country, and have been in contact with Sephardic communities here and around the world for dramaturgical support. We are on the search for our next artistic home and funds to continue to develop the visual language of the piece. Perhaps even as a film!

Here is a description of the show:

Salonika, Greece. 1941. As the Axis powers move into the city, its Sephardic Jewish population begins to experience a small taste of the very real horrors to come. A young boy and girl escape the tensions and trials of the world around them by disappearing into an absurd, magical realm of make-believe. However, this fantasy world is not at all an escape for those who live within it. The prince and princess of this land are equally troubled, eventually escaping into an 'invented' world of the future, where a girl and boy in Salonika (much like themselves) tell stories to ease their pain.

Experimenting with traditional Ladino folklore, the mixing of languages, talking animals, Ottoman shadow puppetry, and musical fusions of middle eastern and electronica sounds, 'Salonika' blurs the line between reality and fiction and explores the multiple - and inevitable - ways in which we are all connected through the power of storytelling.

‘Inşallah / Maşallah’; is there any influence of your Turkish origin in this piece of opera that you have composed?

This was a commission from Target Margin Theater in Brooklyn, NY giving an opportunity to several artists with heritage in the Middle East to reimagine and reinterpret the Sindbad stories from 1,001 Nights.

Part sound installation, part concept album, Inşallah / Maşallah explores the powers and problems of myth in cultural narrative via sound, song, and sensory manipulation. I was very interested to see what kind of story could be told using only sound and lights. The audience is free to move around the space as they wish, focusing on parts of the audio experience that they find most interesting. As for Turkish influence, this piece is full of it. I pulled heavily from the Turkish Makam systems to create melodies, and I sampled saz, kanun, zurna, and many other instruments and rhythmic patterns and to build the score. I also spent a lot of time researching the Turkish 'kuş dili [bird language]' as the basis for one of the sections of the piece. I am hoping to release an album version of the show in the coming year.

Can you give us some information about the 52nd Street Project? What is your role there?

The 52nd Street Project is one of my favorite organizations in New York City. We work with under-served youth in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood, pairing them with theater professionals, to create new and original creative work. Young people have so much to say, from such an interesting, un-edited perspective, and we give them a platform to express themselves in ways they might not otherwise encounter. This can be theater, music, dance, film, poetry, podcasts, etc.

I am the music director there, so I support anything involving music or sound. One program that was particularly successful over the pandemic was our SongMaking program. I worked with four young people, aged 9 through 12 to create four brand-new songs. They wrote the lyrics and I wrote the music and the results are absolutely magical - their brains are so creative and special...

Can you talk a little bit about Jonathan Larson Grant, New Music USA Grant and Anna Sosenko Assist Trust Grant?

The Jonathan Larson Grant is a major award given to individuals or teams who are pushing the boundaries of musical theater in the United States. My collaborator, Julia Gytri, and I were awarded it for our work with SALONIKA.

The grant from New Music USA is towards collaboration with my friend and choreographer, Hadar Ahuvia, for a new piece titled, The Dances Are For Us, which historical investigation and interrogation of Israeli dance.

The Anna Sosenko Assist Trust provides small grants to early-career artists, to be used towards equipment and expenses necessary for their professional development. I am honored to be a recipient of each of these awards!

What awards have you received so far?

I am a Jonathan Larson Grant, New Music USA Grant, and Anna Sosenko Assist Trust Grant winner, and finalist for the Richard Rogers Award. Also, I am a Dramatists Guild Fellow, a commissioned member of the National New Play Network Bridge Program, and have been an Artist-in-residence with: THEatre ACCELERATOR, Goodspeed Musicals, Princeton University, Yale University, Berkeley REP, Exploring the Metropolis at JCAL, MANA Contemporary, Hi-ARTS, Judson, New Dramatists, and Weston Playhouse, among others.

What is it like to be an artist in the 21st century?

It can feel thrilling and impossible at the same time. Never before have we had access to so many, things, ideas, and people to create across borders and cultural divides. But at the same time that can be completely overwhelming. The world moves very quickly now, sometimes too quickly, and it's a big challenge to find moments to slow down, reflect, and process. But on the whole, I'm mostly excited and energized by all the possibilities technology can bring into our process of creation. Either as a necessary component of the work, or as a contrast to something more ancient and primal.

Do you believe music will change the world?

I think music - and art, generally - have changed and will continue changing the world, but more importantly, I think they are uniting the world more than ever before. These mediums give us the tools to express and process the way we feel as people and communities, and to create a platform for various causes to be heard. The shared experiences of creating and consuming art allow people with different backgrounds to understand empathy, and at the very least, to enjoy some beauty in the world so full of turmoil.

Nothing can move people to tears or to pure joy quite like music. A single note can carry the emotional weight of a million words, communicating the history of a whole people and the possibility of a limitless future in one gesture. And it's such a gift to be a composer, and trusted as a caretaker of such treasures.

What do you do in your spare time? Do you have any hobbies?

Most of my spare time right now, like many people, is spent with family. The pandemic has been devastating to our creative industry, especially affecting those without support systems. The one benefit has been all the extra time spent with my wife, Molly, and our almost 2-year-old daughter, Noa, who is growing up so much! Reflecting on this last year, I wouldn’t trade this extra time with them for anything in the world.

We do our best to make time for hobbies, though! I hike in the mountains as much as possible and we have hundreds of plants in our Brooklyn apartment to take care of. I also love to cook - I make my own bread and especially love cooking Turkish food, which I learned from my mother and grandmothers. One day my 'börek' will be as good as theirs and then I can retire….

Müzik konusunda yetenekli gençlere ne yapmalarını tavsiye edersiniz?

This reminds me of a conversation with my cousin, Sibel Horada, while walking up the hill to Hristo Monastery on Burgazada [Burgaz Island], several years ago. It was a cloudy autumn day, and she was taking us for fresh 'gözleme [Turkish flatbread]'. Sibel is a fantastic visual artist and I was seeking advice, as a younger person in the creative field. She said, “The most important thing you can do is to talk to people. It’s your job now. Making art, finding jobs, doing your homework, of course. But the people you connect with and the stories they tell you will become embedded in your work in ways you can’t imagine, so that’s what you have to do.” I think about that conversation often and try to share the sentiment with my students whenever I can.

Related News