The “Chest” Witness of Silent Migrations

“So much so that if this article were not written, something would be missing from the family history and experiences, and the journey from Seoul to Ankara would be erased from minds. This article is also a part of the mourning process and a story of recovery. The chest´s witness to my mother´s family´s migration story makes me want to make this story visible by sharing it. Moreover, I feel like my mother, who does not write her own story, will talk about it here.” - Mutlu Binark

It is known that objects, as physical entities of communication, affect human life as message carriers or as the message itself since existence. Bags, suitcases, and chests, which accompany many migrations and drifts, translate the silent tongues of their owners. These objects carry stories of experiences from person to person across societies throughout history. My fondness for antiques, antique dealers, and auctions has been going on for years, not only in books, ephemera, and printed historical documents but also in objects. In an article I read, I was very impressed by the chest witnessing a migration story and the way this situation was told. I'm sharing this with you. While being a bibliobibuli is getting drunk with books, it also requires turning your eyes to articles and opening new doors. You discover, you expand your knowledge, you open a window from the magical world of books and take a look at what is happening around you, what has happened in time. In this article, I evaluate an article that impressed me in terms of artistic sensitivity, literary style, and success in reflecting loaded emotions. The article in question;

Published in: Türk Folklor Araţtýrmalarý Derneđi Dergisi, 2024, Number:369, 29-67, July 2024. (Published in January and July)

Title Of The Article: “Mum's Chest: A Migration Story and Narrative Legacy from Seoul to Ankara”

Author Of The Article: Prof.Dr. Mutlu Binark, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Communication, Radio, Television and Cinema Division, Informatics and Information Technologies Department

Kamay family with their Korean helper at their home in Seoul

Mutlu Binark, my cousin, states that in this article, she uses the story of her mother Naile Binark's family heirloom Korean chest, covering three generations, as cultural material. She underlines that she traced the narrative legacy carried by the chest through historical studies, images in the photo album, and personal narratives during her mother's family's migration journey from Russia to Korea and Turkey. Mutlu Binark opens literary channels in academic writing and arouses interest. The way she conveys the emotions created by the Korean chest and the research process is impressive. While reading the article, I imagined the Korean chest as a being with living personal characteristics. Welcome to witness the existence of the Korean chest on its migration journey to Turkey, enjoy reading.

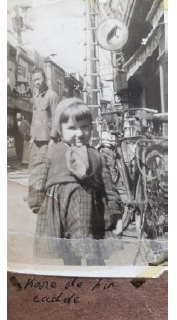

Naile Binark playing on the street in Seoul as a child

Stories of silence in the Korean chest

In her article, the researcher writes that the chest whose story she will tell is an item that her mother's family acquired in Korea, which connects and transcends generations. She states that there is a material history from Korean culture to Tatar culture and from there to Turkish culture. Mutlu Binark says: “The Korean chest has no voice of its own, it cannot speak and give voice to its journeys. But there are stories of silence passed on by those who touch and use the wood of the Korean chest and its shell and mother-of-pearl coverings.” What comes to mind is the suitcases and chests that got old and found themselves in the trash, missing their owners whose personal belongings were plundered during the Second World War. Someone should write their stories too.

Eyebrows that turn white overnight

Mutlu Binark believes that it is necessary to tell the stories of Kazan Tatar families from Russia to the Korean Peninsula in the early 1900s and to embody the stories that the chest carries silently. In her article, the researcher writes that there is no academic study written about the Tatar Diaspora in Korea, which makes it necessary to tell this migration story and says the following; “My grandmother used to read Tatar folk tales, Ţüleli and Water Mother, to me from Tatar illustrated children's books written in the Cyrillic alphabet when I was a child. My aunt first showed me her snow-white eyebrows and said that her eyebrows turned white overnight. The reason for this was that some people from the Tatar colony were imprisoned by the Japanese in occupied Korea. This included herself. If I am not mistaken, she would say that she was helped by a Korean guard or watchman.”

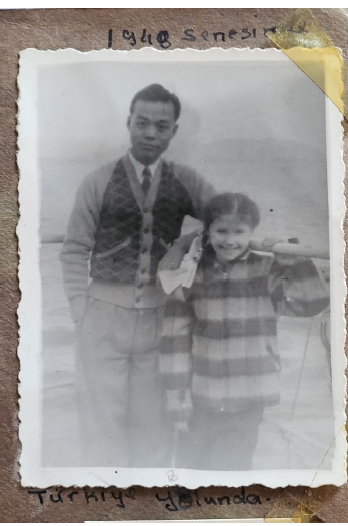

Naile Binark on the ferry they boarded in Hong Kong on the way to Türkiye

Korean chest versus Japanese chest

Mutlu Binark states that her childhood memories include Tatar folk tales and lullabies that her grandmother told and sang. The researcher says that family albums also include weddings, picnics, or religious holiday celebrations sent to each other by Tatars living in Manchuria, Korea, Japan, and Vladivitovsk. The researcher writes that the family albums also include printed materials of theater works, especially Tatar Folk Plays, and postcards printed in the printing house in Tokyo. Article writer and researcher Mutlu Binark sees one of her grandmother's Japanese chests in one of the family photographs taken at home. She points out that the Japanese chest was probably used as a bed-duvet cabinet. In the following lines of the article, it is written that the Korean chest, which has a delicate structure, functions as an ornamental object in the private room of women. She states that sturdy and unadorned Japanese chests can be placed on top of each other by covering them with a cover. As far as I understand, there is a hierarchy between the chests, the Japanese chests do the heavy work, the Korean chests do the delicate work. We get information about the chest in question from the author's pen: “What kind of a chest is it? These chests, which Koreans call "chege", have a furniture made of rosewood. In addition to painting the wood red, brown, or black, it is also decorated with mother-of-pearl obtained from seashells. In addition to traditional Korean patterns, scenes depicting daily life in Korea, mountains, bamboo, forests, and the sun and moon are also embroidered on these chests. I don't know what position the chest has in the house in Seoul. But I think it is in the bedroom, which marks the private area, along with another family heirloom from that period, a small make-up or decoration cabinet with a mirror.”

Mutlu Binark’s first visit to the chest in the Korean Cultural Center, Ankara, 9.2.2024

First visit to the Korean chest

Stating that she and her brother had donated the Korean Chest to the Korean Cultural Center after the loss of his mother, the researcher also states that she visited the chest on display at the Korean Cultural Center for the first time and says the following; “My mother's chest of Korea contains all the memories of the Tatar colony once living there in the Far East, and their settling first in Istanbul and then in Ankara, after a very difficult journey. Telling the story of the chest by bridging the migration of my mother's family in the cultural geography to which it belongs is a way of speaking and a healing process for me. Because this is how the chest lives. My mother and her family, too, with this article.”

You can see the Korean Chest at the Korean Cultural Center in Ankara. You can download and read Mutlu Binark's article and the story of the chest as a PDF from www.turkfolklorarastirmalari.com or academia.edu.

The author of the article says that it is the empty spaces around objects that show them, and I say: "Objects and people want free space for themselves! To be seen, understood and to tell their stories, of course! Everything and everyone that lives has a story, and it is Bibiobibuli's job to read and tell the stories." With friendship.

Related News